- Home

- Brian Callahan

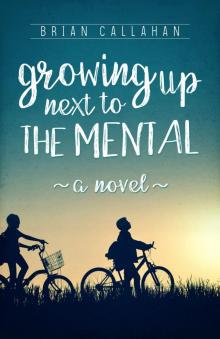

Growing Up Next to the Mental Page 9

Growing Up Next to the Mental Read online

Page 9

He laughed. I almost cried on the spot. It was the first time we’d spoken about it since it happened. I also told him how that bit of mischief had been pinned on a patient, but there was no reaction.

And back came his mother, right on cue—again.

“All ready?”

“Yeah. Sure. Can’t wait,” he replied sarcastically.

He allowed his mother to get a few steps ahead, then turned back with an apparent afterthought.

“Gerald Monchy. Gerry. That’s buddy’s name. Look it up.”

“We have to go, Roddy,” his mother called out.

“‘Wish’ me luck!” he said. “Get it?”

Gerry Monchy. Gerry Monchy. Gerry Monchy.

I kept saying his name over and over in my head until I was sure it was in there good.

Then it hit me. Holy shit. He probably could’ve killed me right there in the Mental Field that day.

Gerry Monchy. Gerry Monchy. Gerry Monchy . . .

What kind of name was Monchy, anyway?

Rodney was gone, but I would most certainly look it up. And I had a pretty good downtown resource to draw from.

I also had a date with the A-B volume of our Encyclopedia Britannica at home in our den.

I had no doubt I’d find a multitude of definitions for bipolar.

The greater task might be finding a good one for “normal.”

13

“Gerry with a G or with a J, my ducky?”

Emily Dickson was like the fairy godmother of newspaper archives. The silver-haired retiree had her own, shall we say, unique filing system that could put stories on hold when she was sick or couldn’t be found.

But when she was in, she was deadly. A needle-in-a-haystack kinda gal.

“It’s with a G . . . I think,” I answered.

I was only allowed to come down to the newspaper after school if it was an “emergency,” which, just like the word “normal,” had yet to be clearly defined in my mind.

“Listen, my ducky, I can’t find anything with Monchy and a homicide,” she called from a stepladder in the back. “I’m afraid it doesn’t ring a bell with me, either.”

She was pushin’ eighty but proved time and again that her memory was still sharp as a tack.

I instantly felt sick, having fallen for the old “mental patient killed a guy” story, hook, line, and sinker. Former PB had gotten me for the last time.

Don’t get me wrong: I was relieved that she’d found nothing to back up what Rodney had said, but also oddly disappointed that the danger and drama of it all had been depleted.

“Did you thank Mrs. Dickson?” my father asked as he whipped his scarf around his neck and topped his head with that godawful Russian fur thing.

I ran back and poked my head in around the corner to her little cubbyhole under the spiral stairs that led to the second floor.

“Thank you!”

“Any time, my ducky.” That was what she called everybody, by the way.

Meanwhile, it had been a week since I’d seen Rodney, and I was still carrying the little newspaper article around in my jacket pocket.

Its presence was all I could think about on the ride home and through supper.

If I gave it to Dad, as instructed, I’d have to tell him the whole story, and he would say exactly what I told Rodney about stories in other newspapers, and our zero responsibility for them.

I suppose a different story could be done about the Janeway and the stuff he was talkin’ about, but the papers didn’t do stories based on outlandish claims from troubled teens in the psychiatric unit, or in a certain orphanage, or a certain home for boys an hour’s drive west on the TCH.

Not yet, anyway. Society was still evolving on that front, too.

The easier and less tangly thing to do was do nothing. If what he said was true, and not just the rantings and ravings of a few shit disturbers trying to get more meds to pop or sell, then it would take care of itself. That’s what all the nurses and doctors were for, and they knew better than me, right?

I was working hard to convince myself that doing nothing was the proper course of action, and I drew on one of Cap’n Mike’s favourite Yogi Berra-isms which always helped guide me through times of indecision: When you come to a fork in the road, take it.

So I did. I took it, and threw the damn article in the garbage. It’s not like I was gonna see Rodney again any time soon. I just had to stay clear of the Janeway.

We couldn’t keep toothpaste in the house after that.

“Looks like someone’s had enough of the dentist for a while,” said Mom, marvelling at my sudden attention to dental detail before bed.

“Yup,” I said through a mouthful of mint-flavoured Crest that sprayed on the mirror as I pronounced the “p.” I now had double the incentive to take care of the few Chiclets I had left, at least until some new ones sprouted.

My mind wandered back to school and how boring it had become with PB out of the picture. There was just too much potential for learning now.

Rodney was right about one thing. Ultimately, neither I nor anyone else seemed to care that he wasn’t there. Especially the Brothers. For them it was simply one less problem kid to deal with. Besides, they were already providing enough bully-supply to power the whole school.

If anything, they probably resented former PB for honing in on their territory. Then again, between the school and the orphanage, the Christian Brothers still had plenty to work with. But for some reason, despite the “open season” label on my forehead, they continued to exclude me from any abuse or punishment.

“Don’t forget your prayers, Aloysius,” my mother called out, ironically.

I knelt down, closed my eyes, intertwined my fingers in a tight clasp, and resumed rationales for the apparent pass I was getting from the Brothers. What the hell was wrong with me? Why was I treated different?

“What was that, darling?” my mother asked as she returned to my room.

“Just finishing off the Our Father,” I fibbed, hopping up and under the sheets.

She leaned over with a peck, adding her dreaded exit phrase.

“Sleep tight. Don’t let the bedbugs bite.”

Why were parents still saying that to their children? It added at least an extra ten minutes of psychosomatic itching and scratching to my usual nod-off time, but I got there.

* * * * *

“So what gives?” I demanded, barging into the principal’s office without asking or knocking.

“How come everyone else is gettin’ the strap except me?”

The line of students waiting for a whuppin’ stretched from his door, back through the reception/waiting area, into the hallway, down the stairs to the first floor, and out onto the steps of the newer Holland Hall section of St. Bon’s.

I tried asking some of them why everyone was in trouble, but I didn’t recognize one soul and no one answered.

That’s when I noticed a plane swoop incredibly low across the campus. It seemed to pull up fast, then stall dead in the air and start to fall tail first back toward the ground.

Okay. This was very familiar.

“Mooney! Get back to class,” shouted the principal, a dead ringer for Mr. Clean, who’d swapped his all-white garb for the black gown of the Brotherhood.

“But Bro. When’s my turn?”

“None for you,” he replied. “You’re normal.”

Dream. Definitely a dream.

The bizarreness of it all—Mr. Clean, the long line, feeling left out ’cause I was the only one not getting the strap, and of course the plane still suspended in mid-air—required the “pinch test.”

And lo and behold, for the first time ever, it worked!

“Oh, thank God,” I whispered to myself as I came around.

I wasn’t sure if it was the pinching or the allegation that I was “normal” that woke me. Nonetheless, I was now more intent than ever to nail down a satisfactory meaning for the word.

For the record, almost every major source was unanimous in the following:

Normal (adj.): Conforming to a standard; usual, typical, or expected.

I knew from that moment that, at least in the technical sense, I—or we—were not normal. Usual, typical, or expected were not the first words anyone would choose to describe the goings-on in our house, our neighbourhood, or around the Mental.

We certainly did not conform to the norm.

Sure, we did “normal” Catholic family stuff like kneeling together in the den every Saturday night before Hockey Night in Canada to say the rosary together. Mass every Sunday, fasting at Easter, Stations of the Cross on Good Friday, etc., etc.

And we were still leaving our doors unlocked at night, despite clear evidence that patients were strolling in at all hours to browse through our seasonal selections of outerwear.

So maybe we were somewhere in the middle? The definition, I found, kept changing from decade to decade.

Still, I needed an independent, non-judgmental third party to put the whole picture into perspective.

“That’s a tough one,” said Cap’n Mike as he lined up the angle for a game-winning shot. “Eight ball, corner pocket.”

He slid the stick back and forth four times before driving the cue ball into the black one, sending it hard into the back of the pocket, down along the wooden ramps, and back to its place in the side of the table.

“I can tell ya what’s not normal,” he said, tossing his stick onto the table in triumph. “The way no one else in this fire hall can seem to shoot a decent game of stick.”

There were a few groans and laughs.

“Tell ya what else ain’t normal—our hours of work, hey boys?”

“Got that right,” said a colleague as he exited the lounge.

Summer, and my paper route, were still a few months away, but I had an open invitation to visit the station any time, as long as they weren’t busy.

“Why all these questions about normal all of a sudden?” he asked, coughing and clearing his throat at the same time, then spitting the mucus mix into a garbage can by the door. I’d shared bits and pieces of Rodney’s antics over the years, but I only ever referred to him as PB, and Cap’n Mike—God love ’im—never pried.

“Well, my PB, we got talkin’ and he mentioned something about ‘bipolar,’ that he had it, and then I looked it up and I think I might, too.”

I, or maybe just kids in general, seemed susceptible to magically contracting the same illnesses as other kids. Or at least convincing themselves they had. I distinctly recall stabbing pains in the right side of my belly for days after middle brother had his appendix out.

“Okay, hold on now, Wish. That’s a pretty serious thing you’re getting into there now. We can talk about lots of things, but you should probably talk to your mom and dad about this one.”

Yeah, right.

“But it said you can be really happy, and then really sad or mad, hard to concentrate, like in school . . .”

“How are you feeling right now?”

“Um, fine I guess. But it says that, too—that you can be ‘normal’ sometimes, too.”

I could tell I had Cap’n Mike’s complete, concerned attention, which must be why the loud familiar blare of the fire alarm physically startled him. It sounded just like the end-of-period buzzer at Brother O’Hehir.

Wouldn’t ya know they’d get a call at that moment.

Despite the mayhem ensuing around us, he squatted down slowly in front of me, placed a hand on my shoulder, and looked directly into my eyes to assure himself I was paying attention.

“As you can see, I gotta go. But do me a favour and don’t worry about being, or not being, normal. Nobody should, ’cause nobody is. So let it go, kiddo. Be true to yourself and you’ll be just fine.”

“Gotta go, gramps,” said one of the other firemen, dropping the hard, white captain’s helmet on Mike’s head backwards.

I carefully walked tight to the walls of the garage area and outside, watching as startled drivers locked up to allow the emergency convoy to scream out onto Topsail Road and off to God knows where.

The consult had been brief, but if nothing else, it was comforting to know that it was normal not to be normal. I think. And that I was far from alone.

I couldn’t help wonder, though, at what point normal ended and the Mental began.

14

Indifferent.

That’s how I claimed to feel about the inevitability of another run-in with one Mr. Monchy. If that was his real name. Maybe “da b’ys” made that up, too.

I mean, if our infallible octogenarian librarian couldn’t find anything on him, there must be nothing to find. And if there’s one thing that was hammered into me as a kid—other than PB’s fists—it was that everyone was innocent until proven otherwise. Cornerstones of the justice and journalism trades.

But just to be on the safe side, I began to forgo my usual shortcuts to Bowring Park through the Mental Field in favour of a piece of municipal infrastructure that people called a “sidewalk.” I don’t know why I hadn’t thought of it before. It eliminated the potential for groin injury while scaling that wobbly, spike-topped fence. And it was just way faster.

Plus, we all knew we shouldn’t be trespassing on private hospital property.

Duh.

But I also knew I couldn’t avoid him or the Mental Field forever, since both were right there. Every hour of every day. A few other characters wandered up from time to time, one of them sporting the biggest set of headphones I’d ever seen, plugged into an old square radio that he cradled like a baby. He also possessed the talent to chew gum and walk like Charlie Chaplin at the same time.

But none of the others could touch Monchy’s routine for originality and presentation. Had he been a figure skater, even the Russian judge would’ve given him a ten. I just prayed that the next time I’d at least see him coming.

He reminded me of the CN train that way, which seemed to have this equally unlikely ability to appear out of nowhere. Loved the train, the way it wound its way through the park, a postcard at every turn. Slowing for safety and emitting short, piercing whistle blasts for kids along the track during the day; longer, distant, and harmonious ones that Dopplered me off to sleep around nine every night.

Every school night, I should say.

But it also could’ve taken any one of our lives at any time on any given day. Whether it was playing chicken with the locomotive on the only trestle in the park, or timing your ride down the steep sliding hill to cross the tracks right in front or just behind as it steamed by.

And let me make this abundantly clear: no train in the history of trains has ever derailed due to pennies, or any other coins, being placed on the tracks for flattening. Not that I knew of, anyway.

But I digress.

As much as I loved hearing and watching the train snake its way through the park every day, it was more fun to hit it with snowballs—mainly for thrill-less target practice, though, since there was zero sound effect and it took no great aim or courage to hit it. It’s not like the engineer was gonna jam on the brakes, jump out, and come after us, either.

There was just no rush involved, unlike right now.

I’d found some friends waiting patiently behind some trees by the tracks near the tennis courts. I joined them, but it was getting pretty boring. So we turned to other moving objects on the road instead, safely sticking with the big-ticket targets like Metrobuses and transports.

But sometimes an innocent, hollow-looking van with potential for a really cool, loud bang was just too tempting to pass up.

Big bang for your chuck, but also life-threatening if they caught ya.

The thrill of the direct hit on this particular day was worth it, though, as the van screeched to a halt and buddy threw open his door.

We never looked back after that, having already dispersed and sprinted off on our varied escape routes, mine naturally taking me up through the Mental Field toward home as I basked in my consequence-free bull’s eye.

That is, until I saw the white victim-van creep around the corner and head up Cowan Avenue toward my house.

I collapsed on my belly, praying I was flat enough in the snow that he couldn’t catch any glimpse of me or the dark blue shade of my snow pants and jacket.

It was only then that the alleged “Mr. Monchy” occurred to me. I’d seen him earlier through the fence, from the sidewalk, so I knew he was somewhere on the go.

I raised my head slightly to survey my immediate surroundings, first spotting the Union Jack and then him a good, safe distance away.

The van had pulled into a driveway across the street, but its reverse lights told me Mr. Persistent wasn’t done yet.

I glanced back to see the flag man approaching, evidently aware of my predicament.

“Don’t worry,” he said, staring off the driver without giving me up. “He’s gone. You’re safe.”

Talk about your ironies.

“Safe for now,” he added with a laugh, but not in that evil-thunderclap-and-lightning kinda way triggered by the Count on Sesame Street, or Frankenstein when he comes to life.

No, his was more silly and exaggerated, like the Carlton Showband’s Laughing Policeman.

I could not believe I’d gotten myself into almost the exact same defenceless position again with this guy. Déjà vu all over again, Cap’n Mike would say.

“Don’t like it vertical, do ya?” buddy quipped.

Growing Up Next to the Mental

Growing Up Next to the Mental